Italian pasta

Foods, Culinary bases, Flour-based foods, Shaped unleavened doughs

Consumption area(s): Italy 🇮🇹

Introduction

Italian pasta, a symbolic staple of the country’s culinary tradition, is made from a non-leavened dough primarily composed of soft wheat flour or semola and liquids such as water or eggs. This base can be enriched with other types of flour, including gluten-free alternatives like rice or legumes, to meet specific dietary needs. Although now enjoyed worldwide, pasta has deep historical roots in Italy, with evidence of its production dating back to the Etruscans. Its preparation involves shaping the dough into sheets or various forms, followed by boiling or baking.

Description of Italian pasta

There are two main types of Italian pasta: dry pasta, typically produced industrially through extrusion, and fresh pasta, traditionally handmade, often with the help of home machines. Both exist in countless shapes—long or short, hollow or flat—and some are designed to be stuffed. In Italy, each shape can have different names depending on the region: for example, cavatelli are known by dozens of local names. There are also decorative or miniature forms, ideal for soups and broths.

From a nutritional standpoint, pasta is rich in complex carbohydrates and contains a fair amount of protein, while being low in fat. It can be made with whole grain or fortified flours, enriched with micronutrients such as B vitamins or iron. Some doughs include alternative ingredients like vegetable purées, cheeses, spices, or even leavining agents, although the latter is rare. Italian pasta is usually made without salt and cooked in salted water, preferably al dente, offering slight resistance when chewed, rather than being soft or overcooked. Certain cooking myths—like the precise temperature or the exact timing of adding salt—lack scientific backing.

Sauce plays a crucial role: each pasta shape calls for a specific dressing that complements its structure. In Northern Italy, sauces tend to be milder, such as béchamel or Bolognese ragù. In the Central Italy, iconic dishes include carbonara, amatriciana, and arrabbiata. In the South, sauces are often made with tomatoes, vegetables, olives, capers and fish.

Lastly, Italian pasta is also featured in broth-based dishes, with shapes like pastina or tortellini, and in rustic soups such as minestrone or legume stews. In all its forms, pasta represents a living tradition, constantly evolving while maintaining its deep ties to the regional and family roots from which it emerged.

History of Italian pasta

The origins of pasta date back to ancient times, long before the word “pasta” appeared in written texts. As early as the Neolithic period, humans had already learned to cultivate grains, grind them, and mix them with water, producing early forms of cooked dough. However, the first true references to pasta in Mediterranean civilizations emerged during Greek and Roman times.

The Greeks used the word láganon to describe flat sheets of dough cut into strips, while makaría and makarṓnia referred to ritual preparations used in funerary rites—terms that still survive in some Southern Italian dialects as maccaruni. In Latin, lagănum referred to a sheet-like preparation, while lasănum was the name of a cooking vessel, from which today’s word lasagna is derived.

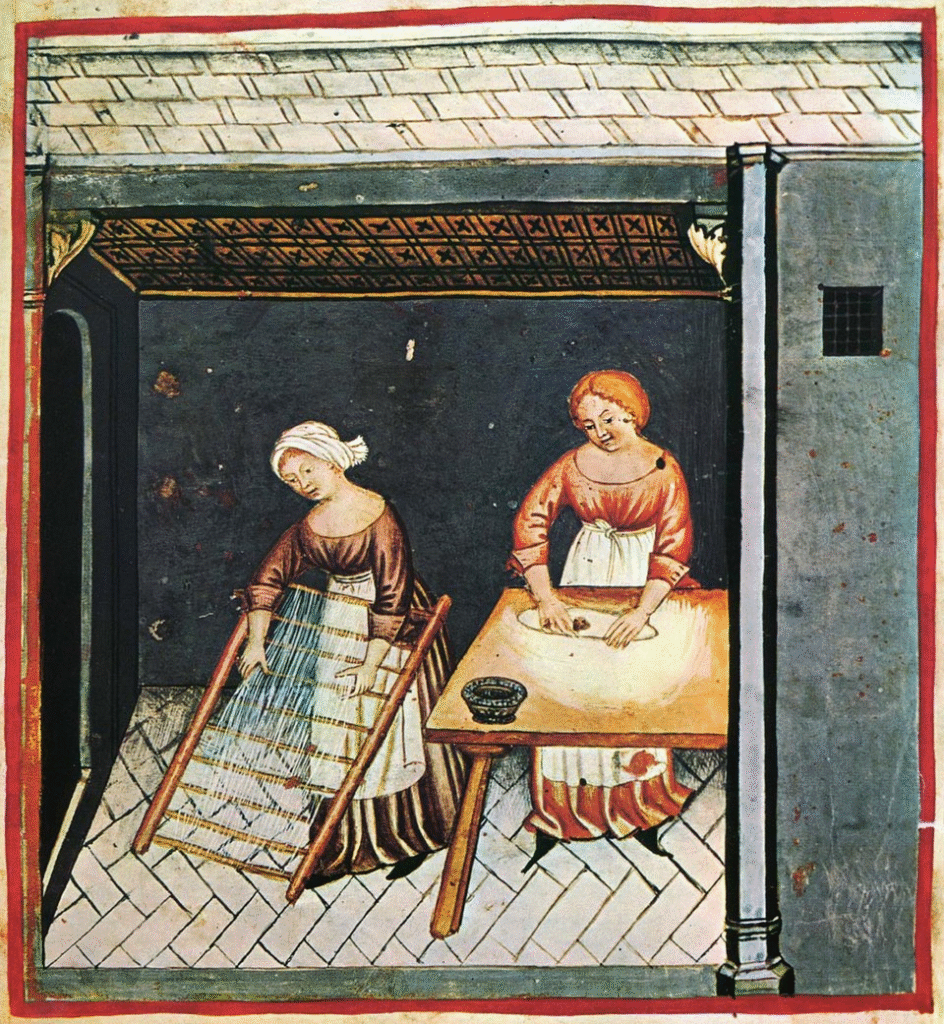

Even during Etruscan times, in Central Italy, there is iconographic evidence of pasta-making. In the so-called Grotta Bella of Cerveteri, we find depictions of tools still used today: kneading boards, rolling pins, and fluted pastry wheels. In the 1st century BCE, Cicero himself mentioned lagane among his favorite dishes. At the time, however, pasta was not yet boiled in water as it is today—it was cooked directly in sauces, a method still present in some Southern recipes.

During the Middle Ages, pasta underwent a major transformation with the development of drying techniques, which made it preservable and suitable for trade. This innovation flourished in Southern Italy, where the dry, breezy climate was ideal for sun-drying. It was in this context that dry pasta began to spread—a form that still characterizes industrial production today. The word pasta, however, first appears in documents in 1051, derived from the Greek pástē, meaning a mixture of flour, water, and salt.

The Arabs played a crucial role in the diffusion and evolution of pasta during their rule over Sicily. Already in the 9th century, the poet and musician Ziryab described preparations resembling pasta. But it was in 1154 that the geographer al-Idrisi provided one of the clearest accounts: in the town of Trabia, Sicily, a thin pasta called itriyya was produced and exported across the Mediterranean—to both Christian and Muslim regions. The word itriyya, of Greek origin (itrion), referred to stretched dry pasta, the ancestor of today’s spaghetti.

Meanwhile, in Central and Northern Italy, people were also making doughs from flour and water. Many local dialects still preserve words like làgana, làina, or làine—all descendants of láganon—linked to fresh pasta dishes, often served with legumes, olive oil, and spices. These recipes retain a direct link to Greco-Roman culinary traditions.

By the 13th century, pasta was already a part of everyday life. A 1279 notarial document by Ugolino Scarpa, from the Marche region, mentions a bariscella plena de maccaroni—a basket full of macaroni. Other records, such as one from 1244, confirm that pasta was being produced, sold, and consumed on a large scale. During this period, the first pasta makers’ guilds were formed, particularly in Southern Italy, organizing production on an artisanal and later semi-industrial scale.

In the 14th century, Giovanni Boccaccio, in his Decameron, described a fantastical land called Bengodi, where vines were tied with sausages, and a mountain of grated Parmigiano served as a base for cooking macaroni and ravioli in capon broth. His tale not only tickled the imagination, but also reflected the central role of pasta in Italian food culture at the time.

In the modern era, macaroni became a symbol of identity. In the 16th century, the macaronic poem emerged—a satirical genre blending Latin and vernacular Italian, championed by Teofilo Folengo. Pasta became so representative of the common people that in the 19th century it drew both praise and criticism: Giacomo Leopardi scorned its popularity, while Gioachino Rossini adored it, even arranging for it to be sent from Rome and Naples, once jokingly signing a letter “Without macaroni”.

With the wave of Italian emigration between the 19th and 20th centuries, pasta became the subject of foreign stereotypes. Italians were often mocked with nicknames like Maccaronì, Spaghettifresser, or Espaguetis, used pejoratively, reflecting a broader climate of anti-Italian sentiment linked to their culinary habits.

In the 1930s, pasta even became the target of ideological attacks. In the Futurist Cookbook Manifesto of 1930, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti called for its abolition, claiming it made Italians weak, unmanly, and unfit for battle. The Fascist regime, aiming to reduce dependence on foreign wheat, supported a push for rice consumption instead. But the campaign ended in farce: Marinetti was eventually photographed eating spaghetti at Biffi’s restaurant in Milan, to the great amusement of the public.

Production methods for Italian pasta

The production of pasta begins with the mixing of soft wheat flour or semola and other key ingredients—typically water or egg—to form a compact, uniform dough. This dough is then kneaded until it reaches the ideal texture. Once ready, it is shaped and cut into various forms, depending on the type of pasta desired. In certain cases, the shaped dough undergoes a drying process, which significantly extends its shelf life, making the pasta more durable and easier to transport.

Cooking Italian pasta

Pasta is primarily cooked through boiling, a method that, in home kitchens, involves bringing water to a boil in a pot. In professional settings, a dedicated pasta boiler is often used. It’s essential to salt the water—about 10 grams of salt per liter—and to maintain the proper ratio of 1 liter of water per 100 grams of pasta. The pasta should only be added once the water is at a rolling boil. During cooking, it is crucial to stir frequently to prevent the pasta from clumping.

Traditionally, the water should remain boiling throughout the cooking process. However, pasta can also be cooked with the heat turned off, as long as the temperature doesn’t fall below 80°C. Cooking time ranges from 3 to 15 minutes, depending on the shape and type of pasta, and it significantly impacts the dish’s digestibility. The term “al dente” refers to a moderate level of doneness—the pasta is tender yet firm to the bite, offering a slight resistance when chewed.

After cooking, an essential step is the mantecatura: combining the pasta with its sauce or seasoning. This can be done cold (as in pesto-based dishes) or hot, by tossing the pasta in a pan with the sauce. For a richer result, a fat-based ingredient (such as butter or oil) or grated cheese can be added at the end to bind everything together.

Pasta can also be served cold, in dishes like pasta salads, where it’s mixed with a variety of ingredients to taste. Another classic is pasta in broth, which includes fresh, dried, or filled pasta served in a meat or vegetable broth. Pastina is a tiny dry pasta format typically used in soups and broths. Another popular method is baking, where pasta is partially cooked, dressed, and then finished in the oven. This step is essential in traditional recipes such as lasagna or timballo.

Fried pasta, though less common in Italy, appears in both sweet and savory dishes. In Naples, the frittata di maccheroni is a well-known example, while in ciceri e tria, fried pasta is combined with chickpeas. In Sicily, there are also sweet fried pasta recipes, often coated with honey and spices.

Classification of Italian pasta

This product is classified according to its shape. Among the most common types are:

- Mezze maniche

- Penne rigate

- Reginette / Mafalde

- Rigatoni

- Spaghetti

Recipes that use this product as an ingredient:

Photo(s):

1. David Adam Kess, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

2. Giorgio Sommer, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons