Cheeses

Food, Animal source foods, Dairy products

Consumption area(s): Earth

Introduction

Cheeses are foods made from milk, created through the coagulation of caseins, one of their main proteins. They come in a wide variety of flavors, shapes, and textures, and can be made from cow’s, sheep’s, goat’s, or buffalo’s milk. During production, cultures and rennets—either animal or plant-based—are used to separate the solid curds, which become cheeses, from the liquid whey. Some types undergo aging and develop distinctive molds, which grow either on the rind or within the cheese bodies.

Description of cheeses

There are hundreds of types of cheese around the world, each with its own distinctive features shaped by factors like the type of milk, the aging process, fat content, the use of specific bacteria or molds, and unique production techniques. Ingredients such as spices, herbs, garlic, berries, or black pepper are often added to enhance flavor. The role of the cheesemaker or a skilled cheese vendor is crucial in the selection, storage, and refinement of the product.

Cheese is highly valued for being nutritious, rich in calcium, phosphorus, fats, and proteins, and it has a much longer shelf life than milk. Hard cheeses (like Parmigiano) tend to keep longer than soft cheeses (like Brie). To fully appreciate their aroma and texture, cheese should ideally be served at room temperature, since cold can mute flavors and cause the fat to harden.

When heated, cheese undergoes structural changes: around 30 °C (86 °F), the fats begin to rise to the surface, while between 55 and 80 °C (131–176 °F), many types begin to melt, turning from solid to fluid. However, acid-set cheeses (like paneer or halloumi) resist melting and simply become firmer. Some cheeses, like raclette, melt smoothly, while others may stretch or separate. To achieve a more stable melt, acids or starches are often used—as in fondue, where wine helps create a creamy texture.

Once cooked, many cheeses solidify again, losing some of the oils released during melting. The saying “you can’t melt cheese twice” comes from this very phenomenon. If the temperature continues to rise, cheese begins to brown and can even burn, developing rich aromas that are especially prized in baked dishes like gratins.

History of cheeses

Cheese is one of the oldest known foods made by humans, predating any form of written history. Its origins remain uncertain, with multiple regions—including Europe, the Middle East, and Central Asia—claiming to be its birthplace. The earliest hypotheses place the discovery around 8000 BCE, when humans first began to domesticate sheep. It’s likely that cheese was discovered by accident, perhaps when milk was stored in containers made from animal stomachs. These natural vessels, containing rennet, would have triggered the separation of curds and whey. A well-known legend tells of an Arab merchant who, while transporting milk in such a container, unwittingly created cheese through this very process.

The oldest archaeological evidence of cheese-making was found in Kuyavia, a region in present-day Poland, dating to around 5500 BCE, where strainers containing milk fat residues were unearthed. Another early clue comes from the Dalmatian coast (modern Croatia), dated to around 5200 BCE. It’s possible that other populations, independently of these findings, had already begun using pressing and salting techniques to preserve curd for longer periods. In Egypt, tomb paintings from around 2000 BCE depict cheese-making, while a 2018 study identified actual cheese remnants in tombs dating to 1200 BCE. In China, the oldest preserved sample was found among the mummies of the Xiaohe cemetery, dated to 1615 BCE.

The earliest cheeses were likely very salty and acidic, similar to ricotta or feta. In the cooler climates of Europe, the lower need for salt allowed the growth of beneficial molds and bacteria, paving the way for the development of aged cheeses. In Greek mythology, cheese was credited to Aristaeus, while Homer, in the Odyssey, describes Polyphemus curdling milk from sheep and goats. During the Roman era, cheese was both widespread and valued. Columella, in De Re Rustica, outlines the steps of cheese-making in detail, and Pliny the Elder praises various types, especially those from Nîmes, the Apennines, and Bithynia. Some, like the Ligurian cheese, reportedly reached extraordinary sizes.

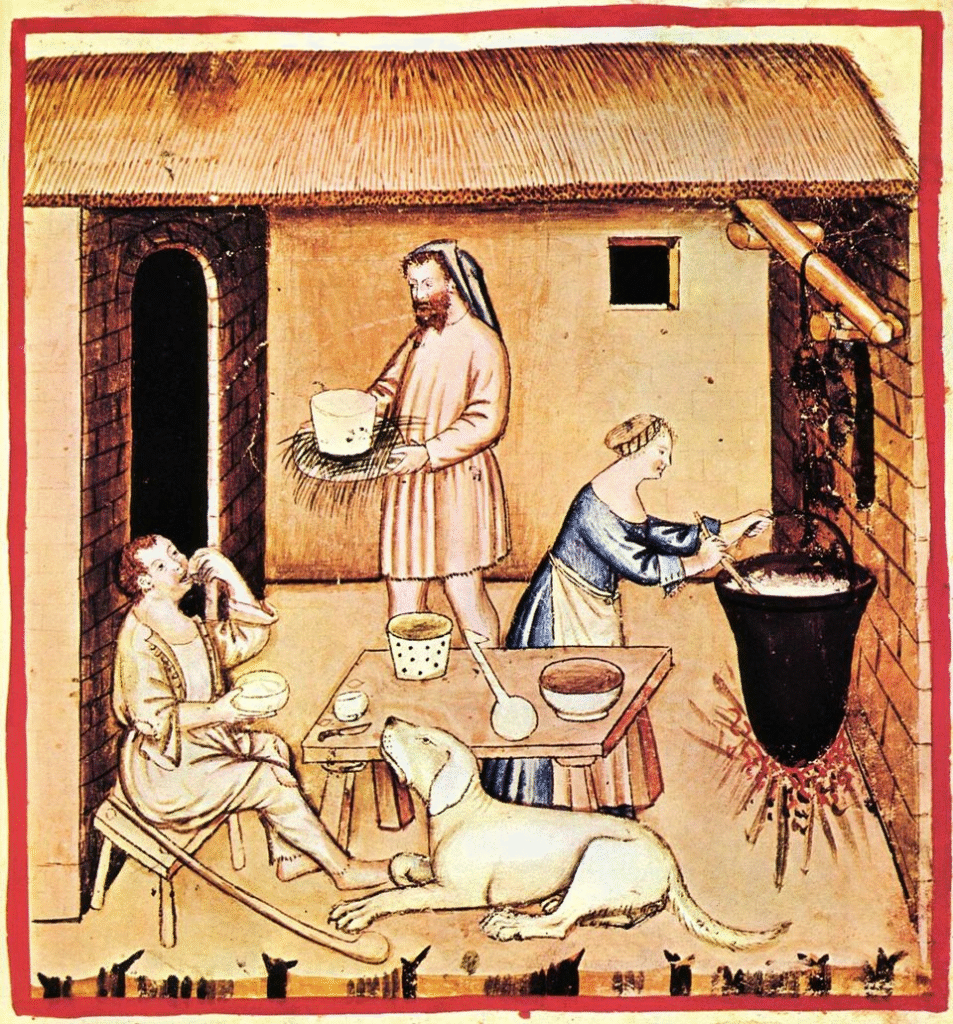

In the medieval period, cheese production continued to evolve. Records mention places like Ceswican, an English village whose name means “cheese farm,” and documents from 1022 describe how Wallachian shepherds from Thessaly supplied cheese to Constantinople. Many modern cheeses trace their roots back to this period: Cheddar around 1500, Parmigiano in 1597, Gouda in 1697, and Camembert in 1791.

It was only with European colonial expansion that cheese began to spread globally. Before that, it was virtually unknown in many parts of East Asia and pre-Columbian America, and had a limited presence in Africa. The first cheese factory was established in Switzerland in 1815, but the true industrial leap occurred in the United States, where in 1851 a New York farmer named Jesse Williams introduced a production line for Cheddar, pioneering mass production. This led to the rise of numerous dairy cooperatives.

In the late 19th century, major innovations transformed the industry: large-scale rennet production and the development of pure bacterial cultures allowed for the standardization of processes. Previously, bacteria came from the environment or leftover fermentations. After World War II, industrial cheese production overtook artisanal methods, becoming the dominant source of cheese in both Europe and North America.

Production method for cheeses

Coagulation is one of the fundamental steps in transforming milk into cheese. During this phase, the milk is separated into a solid part, the curd, and a liquid part, the whey. This separation can be achieved through acidification, either by adding acids directly—such as vinegar, a common practice in fresh cheeses like paneer—or through the action of lactic acid bacteria, which convert lactose into lactic acid. The latter method is the most widespread and involves microorganisms such as Lactococcus, Lactobacillus, and Streptococcus, which also contribute to developing the aromatic profile of long-aged cheeses.

In specific cases, like Emmental, particular cultures such as Propionibacterium freudenreichii are used; these bacteria produce carbon dioxide during aging, creating the characteristic holes (or “eyes”). Many fresh cheeses are made solely through acidification, but most varieties also involve the addition of rennet (which coagulates milk at a lower acidity), making the curd more firm and elastic. This is crucial because an overly acidic environment would inhibit the bacteria responsible for flavor development. Generally, softer and younger cheeses are coagulated at higher acidity levels, whereas harder and aged cheeses require more rennet.

Today, rennet is mostly produced through biotechnological methods, but originally it was extracted from the mucosa of the stomachs of milk-fed calves.

Once the milk coagulates, it forms a soft, moist mass. In soft cheeses, the curd is simply drained and salted; in hard cheeses, the curd is cut into cubes to facilitate the expulsion of whey, often combined with heating between 35 and 55 °C, which speeds up liquid separation and influences the final flavor. Other cheeses, like Italian ricotta, are made from whey rather than curd.

Salt is added either directly or by immersing the curd in brine to enhance flavor, preserve, and remove moisture, making the curd firmer. Subsequently, a series of specific methods for producing certain cheeses may be applied, which will be detailed on their dedicated page.

Freshly made cheese can be rubbery and mild in taste, although in some cases, this texture is desired. More often, however, the cheese undergoes ripening: it is left to rest for a period ranging from a few days to several years in controlled environments. During this time, enzymes and microbes transform milk components—especially casein and fat—generating a complex array of aromatic compounds such as amino acids, amines, and fatty acids. Many cheese types also incorporate specific molds or bacteria, either naturally present or intentionally added.

Classification of cheeses

The classification of cheeses is quite complex, mainly due to the lack of a single unifying criterion. Therefore, a series of overlapping classification criteria are used:

Source of the milk:

- Buffalo cheeses

- Cow (bovine) cheeses

- Goat cheeses

- Mixed milk cheeses

- Sheep cheeses

Moisture content:

- Hard cheeses

- Semi-hard cheeses

- Semi-soft cheeses

- Soft cheeses

Mold characteristics:

- Cheeses with internal mold

- Soft-ripened cheeses

- Washed rind cheeses

Special production methods:

- Cooked pressed cheeses

- Pasta filata cheeses (stretched-curd)

Special preservation methods:

- Brined cheeses

Milk treatment:

- Raw milk cheeses

Type of coagulated product:

- Whey cheeses

The first two categories (source of milk and moisture content) are considered complete, as every cheese falls into one of these groups. The other categories, such as molds and special production methods, describe specific features of the production process or the final product, and do not apply to all cheeses.

In theory, for each of these categories, an opposite category could be introduced (e.g., “cheeses without molds,” “cheeses without special production methods,” “cheeses without special preservation methods,” “cooked milk cheeses,” “curd cheeses”), but this would not be practical or descriptive.

Therefore, it is preferred to keep these categories incomplete, applying them only when the characteristic is present. For example, if a cheese is not described under any of the mold categories, it is simply assumed that it does not contain molds, without explicitly stating so.

For better understanding of this classification, below is a filter where you can select the various criteria, and a list of cheeses matching those criteria will appear.

Source(s):

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cheese

Photo(s):

1. Daderot, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

2. unknown master, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

3. No machine-readable author provided. MatthiasKabel assumed (based on copyright claims)., CC BY-SA 3.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/, via Wikimedia Commons