Celery

Subpecies of Apium graveolens

Food, Plant source foods, Flowering plats (angiospermae), Mesangiosperms, Eudicots, Core eudicots, Superastierds, Asterids, Campanulids (Euasterids II), Apiales, Apiaceae, Apium, Apium graveolens

Subspecies name: Apium graveolens var. dulce

Consumption area(s): Earth

Note: For better understanding, please read the article on flowering plants (angiospermae) first. If you come across unfamiliar words, you can click on any highlighted term to open the glossary with definitions of key botanical terms.

Introduction

Celery, botanically classified as Apium graveolens var. dulce, is a domesticated form of Apium graveolens within the Apiaceae family and has been incorporated into human dietary practices as a vegetable since early historical periods.

Description of celery and its edible parts (leaves, leaf stalk, hypocotyl and seeds)

Celery displays compound foliage ranging from pinnate to bipinnate, with rhombus-shaped leaflets of moderate size. Its flowers are small, creamy white, and grouped in compact compound umbels, while the so-called “seeds“—botanically small fruits—are ovoid to nearly spherical. Contemporary varieties have been deliberately developed to emphasize specific traits, such as thick, fleshy petioles, enhanced leaf production, or an enlarged hypocotyl. A distinctive feature of the stalk is its tendency to split into fibrous “strings”, which are bundles of collenchyma cells positioned outside the vascular tissue.

As a food plant, celery is consumed globally, though preferences vary by region. In North America and much of Europe, the crunchy leaf stalks are the primary edible part, whereas in parts of Europe the swollen hypocotyl is also valued as avegetable. Celery plays a foundational role in several classic culinary bases, including the Louisiana Creole and Cajun “holy trinity” with onions and bell peppers, and the French mirepoix alongside onions and carrots.

The leaves themselves are often employed to impart a mildly spicy note, reminiscent of but gentler than black pepper. They can be used fresh or dried, added to meat and fish dishes, mixed into soups, or even eaten raw in salads or as a garnish.

In temperate regions, celery is also cultivated for its seeds, which yield an essential oil used in the perfume industry and containing the compound apiole. The seeds function as a culinary spice, either whole or ground. When combined with salt, they produce celery salt, a seasoning widely used in cocktails such as the Bloody Mary, in regional foods like the Chicago-style hot dog, and in blends such as Old Bay Seasoning. Mixtures of celery powder and salt are additionally employed in meat curing, where the plant’s naturally occurring nitrates interact with salt to aid preservation.

In recent years, celery has also gained attention through the popularity of celery juice. Around 2019, claims promoting its supposed detoxifying effects circulated widely in the United States, despite lacking scientific support, leading nonetheless to a noticeable increase in market demand and prices.

History of celery as food

Celery has a long and intricate history, with evidence of its presence reaching back to ancient Egypt. According to scholars Daniel Zohary and Maria Hopf, celery leaves and flowers were discovered woven into funerary garlands inside the tomb of Pharaoh Tutankhamun (who died in 1323 BCE). In addition, celery seeds dated to the 7th century BCE were found in the sanctuary of Hera on Samos. However, because wild celery grows naturally in that region, it remains uncertain whether these finds came from cultivated plants or wild populations. Only in the Classical period can celery be confidently identified as a crop under systematic cultivation.

Further archaeological evidence suggests that celery was already present by the 9th century BCE, as shown by discoveries at Kastanas, yet it is within ancient Greek literature that references become especially frequent. In the Iliad, Homer depicts the horses of the Myrmidons feeding on wild celery in the marshes of Troy, while in the Odyssey, the meadows surrounding Calypso’s cave are described as abundant in violets and wild celery. During the Middle Ages, the Capitulary of Charlemagne (around 800 CE) lists celery among the plants to be cultivated, although at first it was largely overshadowed by alexanders, a closely related aromatic herb that later gave way to celery in European cuisine.

Celery’s late adoption in English cooking was largely due to the lengthy selective breeding process required to reduce its natural bitterness and enhance its sweetness. In 1699, John Evelyn recommended it in his treatise Acetaria. A Discourse of Sallets, praising it as a refined vegetable, comparable to Macedonian parsley, valued for its rich, elegant flavor and particularly suited to salads.

In the United States, celery initially played a minor role in colonial gardens and was regarded merely as a type of parsley. It was only in the 19th century, following improvements that enhanced its crisp texture and flavor, that celery became a luxury food. It was often presented in specialized celery vases, allowing diners to season it with salt and eat it raw. Throughout the 19th century and into the early 20th century, celery grew so popular that it ranked as the third most common item on New York restaurant menus, surpassed only by coffee and tea.

Production methods of celery

Celery is primarily grown from seed, which may be sown in heated seedbeds or directly in the garden soil, depending on seasonal conditions. After one or two rounds o transplanting, the young plants, once they reach a height of 15–20 cm, are set into deep trenches to encourage blanching. This traditional practice involves earthing up the soil around the stalks to block light exposure, thereby improving stem texture and flavor. In modern agriculture, however, self-blanching celery varieties, which eliminate the need for ridging, have become predominant in both home gardening and commercial production.

Historically, celery was cultivated as a seasonal vegetable, especially during winter and spring, when diets heavy in salted meats often led to nutritional deficiencies. At such times, celery was valued for its reputed cleansing properties. During the 19th century, the harvest season in England expanded significantly, making celery available from September through late April. When marketed, celery is typically sold without roots, though a small portion of green leaves is usually retained.

In commercial harvesting, celery is collected once plants reach an optimal and uniform size, ensuring consistent quality. Selection criteria focus on color, straightness, and stalk thickness. Because growth within a field is highly uniform, harvesting is generally carried out in a single pass. The produce is packed in crates containing 36 to 48 stalks, with a total weight of up to 27 kg. When stored at temperatures between 0 °C and 2 °C, celery can remain fresh for up to seven weeks, and its shelf life may be further extended through shrink-wrapping in microperforated film.

Nutritional facts table of the stalk and the hypocotyl

| Nutrients | Per 100 g |

| Calories (kcal) | 16 |

| Total fat (g) | 0.17 |

| ———Saturated fat (g) | 0 |

| Cholesterol (mg) | 0 |

| Sodium (mg) | 80 |

| Total carbohydrates (g) | 2.97 |

| ———Dietary fiber (g) | 1.6 |

| ———Total sugar (g) | 1.34 |

| Protein (g) | 0.69 |

Recipes that use this product as an ingredient:

Photo(s):

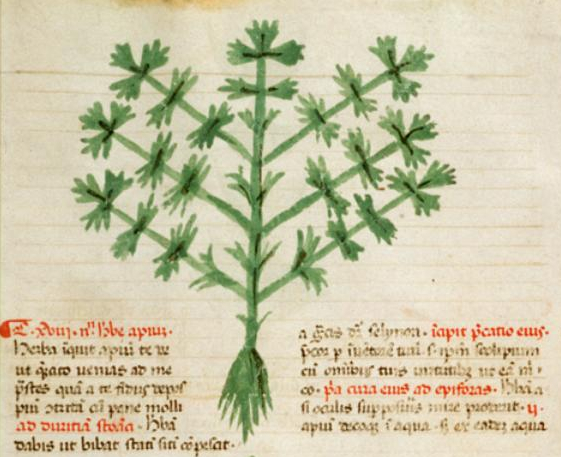

1. Lombroso, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

2. Apuleius, Barbarus — Herbarium, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons