Wines

Food, Plant source foods, Alcoholic beverages, Fermented alcoholic beverages

Consumption area(s) (countries that consumed more than 5 L per persone annually in 2022): Algeria 🇩🇿, Andorra 🇦🇩, Antigua and Barbuda 🇦🇬, Argentina 🇦🇷, Australia 🇦🇺, Austria 🇦🇹, Bahamas 🇧🇸, Barbados 🇧🇧, Belgium 🇧🇪, Belize 🇧🇿, Belarus 🇧🇾, Bosnia and Herzegovina 🇧🇦, Botswana 🇧🇼, Bulgaria 🇧🇬, Canada 🇨🇦, Cape Verde 🇨🇻, Chile 🇨🇱, Costa Rica 🇨🇷, Croatia 🇭🇷, Cyprus 🇨🇾, Czech Republic 🇨🇿, Denmark 🇩🇰, Dominica 🇩🇲, Estonia 🇪🇪, Finland 🇫🇮, France 🇫🇷, Georgia 🇬🇪, Germany 🇩🇪, Greece 🇬🇷, Grenada 🇬🇩, Guinea-Bissau 🇬🇼, Hungary 🇭🇺, Iceland 🇮🇸, Ireland 🇮🇪, Italy 🇮🇹, Japan 🇯🇵, Latvia 🇱🇻, Liechtenstein 🇱🇮, Lithuania 🇱🇹, Luxembourg 🇱🇺, Maldives 🇲🇻, Malta 🇲🇹, Mauritius 🇲🇷, Moldova 🇲🇩, Monaco 🇲🇨, Mongolia 🇲🇳, Montenegro 🇲🇪, Namibia 🇳🇦, Netherlands 🇳🇱, New Zealand 🇳🇿, North Macedonia 🇲🇰, Norway 🇳🇴, Paraguay 🇵🇾, Peru 🇵🇪, Poland 🇵🇱, Portugal 🇵🇹, Qatar 🇶🇦, Romania 🇷🇴, Russia 🇷🇺, Saint Kitts and Nevis 🇰🇳, Saint Lucia 🇱🇨, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines 🇻🇨, San Marino 🇸🇲, São Tomé and Príncipe 🇸🇹, Serbia 🇷🇸, Seychelles 🇸🇨, Slovenia 🇸🇮, Spain 🇪🇸, South Africa 🇿🇦, Sweden 🇸🇪, Switzerland 🇨🇭, Trinidad and Tobago 🇹🇹, Tunisia 🇹🇳, Turkmenistan 🇹🇲, United Kingdom 🇬🇧, United States of America 🇺🇸, Uruguay 🇺🇾, Vatican City 🇻🇦

Introduction

Wine is an alcoholic beverage derived from the fermentation of grape juice. It is crafted and enjoyed across the globe, exhibiting a remarkable diversity of styles shaped by the grape varieties, climate, vineyard practices, and production methods employed. Historically, wine has held a significant place in religious rituals and spiritual practices, while also serving as a prominent inspiration in art and culture throughout the ages. It is commonly consumed on its own or paired with food, particularly in social environments like wine bars, restaurants, or formal gatherings.

The evaluation of wine is a sophisticated activity, with connoisseurs employing a wide array of descriptive terms to capture its aroma, flavor, and texture. Many enthusiasts also collect and age wine, either as a form of investment or to allow it to develop complexity over time. While wine contains alcohol, making excessive consumption potentially harmful, moderate intake has been associated with certain cardioprotective effects, offering a nuanced balance between enjoyment and health considerations.

Description of wines

Wine is produced through the fermentation of grapes, which can be either partial or complete. Alternatively, grape must can also be used. Wine can be made from grapes derived from crosses between Vitis vinifera and other Vitis varieties, such as Vitis labrusca or Vitis rupestris, or even from grapes of other species like Vitis chunganensis.

Across the European Union, the term “wine” is legally reserved exclusively for products obtained from the fermentation of Vitis vinifera grapes. Consequently, beverages fermented from other grape varieties cannot be labeled as wine. To navigate this restriction, producers often simply indicate the grape variety used, avoiding the word “wine” altogether.

From a chemical perspective, wine is primarily a mixture of water and ethanol, but it also contains other compounds that may offer health benefits, such as polyphenols and anthocyanins. Conversely, some substances, like sulfur dioxide, are considered undesirable and potentially harmful, which is why their concentration is strictly regulated by law.

Wine plays a significant role in cooking, serving not only as a way to soften ingredients during preparation but also as a key source of aroma in dishes like marinades, broths, hearty stews such as coq au vin or beef bourguignon, and in various wine-based sauces. It also appears in numerous desserts, including classics like zabaione and trifle. Since ethanol boils at about 78 °C (172 °F), heating wine beyond this temperature typically removes most of its alcohol, allowing its acidity and natural sugars to stand out more clearly.

There is ongoing discussion about what level of quality a wine should have to be suitable for cooking. What is certain, however, is that wine with defects is unsuitable, and the more nuanced flavor compounds found in high-quality bottles generally do not withstand prolonged heating.

History of wines

In 1996, a significant archaeological discovery was made at Hajji Firuz Tepe, a Neolithic village in northern Iran, during an excavation led by the University of Pennsylvania. Among the artifacts uncovered was a terracotta jar dating back to 5100 BCE, containing a dry powder derived from grape clusters. This finding suggests that the fermentation of grapes and the initial production of wine may have occurred accidentally as far back as 9,000–10,000 years ago, likely due to errors in grape storage.

The large-scale production of wine appears to have begun around 4100–4000 BCE, marked by the identification of the first winery in Areni, located in present-day Armenia. This event represents the start of a tradition that gradually solidified over the following centuries. The earliest historical records concerning vine cultivation date to 1700 BCE, but it was with the rise of Egyptian civilization that viticulture became more structured, enabling widespread wine production.

In the Bible, the Book of Genesis recounts that Noah discovered the process of winemaking after the Great Flood. According to the story, he planted a vineyard, produced wine, and became intoxicated. In Christian tradition, wine has become a symbol of the blood of Jesus Christ, as during the Last Supper, Jesus referred to it as the symbol of the new covenant, poured out for the forgiveness of sins. Wine continues to hold a central role in Catholic liturgy, particularly in the Eucharist.

During the Roman Empire, wine production underwent substantial expansion. Once a luxury product reserved for the elite, wine became a daily beverage. Vine cultivation techniques spread widely across the Mediterranean, including Italy, Spain, France, and other regions, boosting consumption.

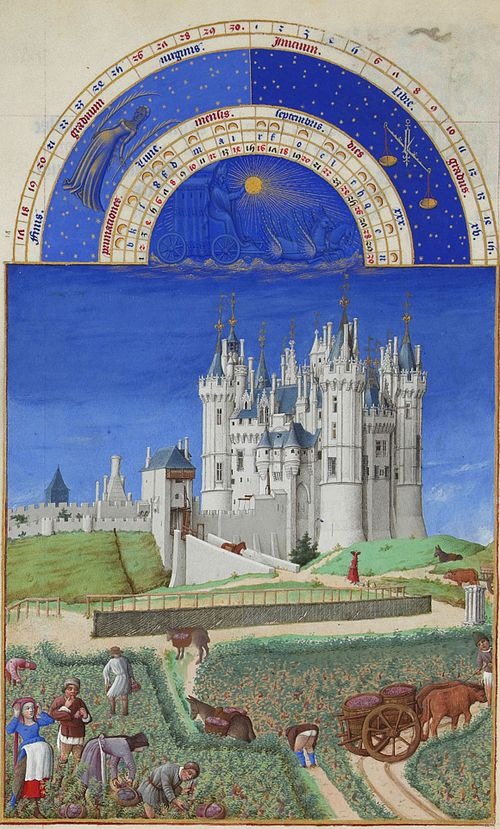

However, the wine of the period was markedly different from modern varieties: due to rudimentary winemaking methods, it was often much sweeter and stronger in alcohol, frequently diluted with water and flavored withhoney andspices. After the fall of theRoman Empire, viticulture experienced a period of decline, but during the Middle Ages, the Church played a pivotal role in its revival, with Benedictine and Cistercian monks improving cultivation and production techniques, practices that largely endured into the modern era.

Production methods for wines

The word wine generally designates a beverage produced by fermenting grape juice, while drinks derived from other fruits fall into the broader category of fruit wines. This group excludes beverages based on starches, honey, or fruits like apples and pears, and it does not include liquids later distilled into spirits. Most non-grape fruits contain too little sugar, too much acidity, and insufficient yeast nutrients, so producers must intervene more extensively. These wines rarely age well and usually remain drinkable for less than a year, though they are particularly popular in North America and Scandinavia.

A wine’s sweetness depends on the amount of residual sugar left after fermentation. Dessert wines maintain a high sugar level, achieved through methods such as using botrytized grapes, harvesting fruit that has frozen, or drying grapes to concentrate their sugars, as seen in Sauternes, icewine, and Vin Santo. Sparkling wines, which contain dissolved carbon dioxide, are typically produced through a secondary fermentation in sealed containers. Approaches range from the traditional method used for Champagne and Cava to the Charmat method used for Prosecco and Asti, with hybrid and inexpensive carbonation methods also in use.

Most wines derive from varieties of Vitis vinifera, including Chardonnay and Cabernet Sauvignon, often grafted onto North American rootstocks for protection against phylloxera. In viticulture, terroir captures the influence of soil, topography, and climate, producing major differences in wine quality and style. Grapes thrive mainly between 30° and 50° latitude, though shifting climates and improved techniques are expanding viable regions, from Sarmiento in southern Argentina to the Okanagan Valley in Canada.

Wine production begins with the harvest, guided by ripeness, acidity, crop health, and weather. Grapes are sorted, destemmed, crushed, and sometimes briefly macerated before pressing. Fermentation typically occurs in steel, wood, or concrete vessels, using either natural or selected yeasts to convert sugars into alcohol and carbon dioxide. Winemakers may adjust tannins (plant-based compounds in wine that make your mouth feel dry and add structure), sugar, or acidity depending on legal allowances, and many wines undergo malolactic fermentation to soften acidity. Before bottling, they may be filtered and treated with sulfites.

Wine is mainly packaged in glass bottles—often 75 cl—with thicker designs for sparkling wines due to their high internal pressure. Although natural cork has been the traditional closure, issues with cork taint and rising demand have encouraged alternatives such as screwcaps and synthetic stoppers, each with different advantages and drawbacks. Other formats include bag-in-box, aluminum cans, and stainless steel kegs used for wine on tap.

Wine serving and tasting

Decanting is used to separate wine from sediment, especially in older bottles, by transferring it briefly into another vessel. This process can also expose younger wines to air, helping them release more aromatic components, while older wines risk rapid oxidation if aerated too much.

Serving temperatures greatly affect perception. Tannic reds are best slightly warm, roughly 15–18 °C (59–64 °F), while structured dry whites benefit from a moderately cool range, around 12–16 °C (54–61 °F). Lighter reds intended as refreshing options are usually chilled to 10–12 °C (50–54 °F). Sweet, sparkling, or otherwise delicate whites and rosés—and wines showing minor faults—are better served at even lower temperatures, about 6–10 °C (43–50 °F).

Classic guidelines suggest serving red wines at the cooler “room temperature” of the past, with whites and sparkling wines progressively cooler. Warmer conditions increase the release of volatile aromas, but temperatures above 20 °C (68 °F) intensify alcohol vapors, and sparkling wines lose carbon dioxide too quickly when overly warm. Heat amplifies perceived sweetness, so wines with limited acidity taste more balanced when chilled. Cooler service mutes aromas—useful for reducing the perception of flaws—but sharpens tannins and bitterness.

Wine tasting involves a structured sensory assessment in which the taster evaluates a wine’s appearance, smell, and flavor. This practice occurs in many contexts, from casual encounters to formal blind tastings. The first visual clues include cloudiness or unexpected bubbles, both of which may suggest faults. Color can hint at age, since reds gradually lighten and whites tend to deepen, while the “legs” that form on the glass after swirling often point to higher alcohol or sugar.

A wine’s nose provides most of its identifiable character, with descriptors ranging from fruit or vegetable notes to more unconventional aromas such as leather or compost. These qualities may arise from the grape variety, fermentation, or aging. Off-odors typically indicate a problem. On the palate, tasters gauge sweetness, acidity, bitterness, tannic structure, and alcohol, along with saltiness in special cases like sherry. After swallowing or spitting, the persistence of flavor—the finish—is an important marker of quality.

Wine and food pairing

Pairing wine with food involves matching a dish and a bottle so that each heightens the other’s qualities. Across many culinary traditions, this pairing emerged naturally: local meals were served with local wines, long before anyone attempted to formalize rules. Only in recent decades has the modern “art” of pairing taken shape, generating books, media, and professional guidance from sommeliers. The core idea is that characteristics such as flavor, aroma, and texture interact, yet pleasure remains subjective—what feels like a “perfect match” to one person may seem far less appealing to someone else.

A fundamental principle for most experts is the relationship between the weight of the food and the body of the wine. A rich, assertive wine like Cabernet Sauvignon can overshadow a light dish, while a delicate wine like Pinot Grigio can vanish next to something hearty. Once weight is considered, pairings can also be guided by whether flavors and textures should be contrasted or complemented. Additional elements—acidity, alcohol, tannins, and residual sugar—may subtly shift how a wine behaves with certain foods.

The notion of weight applies to both components of a dish and its overall intensity. Identifying the dominant flavor is essential: sauces, for instance, may dictate the pairing more than the protein itself. A mild fish might call for a light white wine, but when enriched with a heavy cream sauce, it may work better with a fuller-bodied white or even a gentle red. Cheese pairing exemplifies how crucial this concept can be, as cheeses vary widely in structure and strength. Soft cheeses tend to suit crisp whites or light reds; bloomy-rind cheeses pair well with traditional-method sparkling wines; semi-soft cheeses match fuller whites; and aged, hard cheeses often shine alongside Sherry or complex reds such as Barolo or Bordeaux.

Wine body itself ranges from light to heavy and is shaped by factors such as alcohol, tannins, and the winemaking process. For example, Pinot Noir may be feather-light or moderately full depending on style, while warm-climate regions typically yield wines with more body. Thus, a Sauvignon Blanc from California often feels weightier than one from the Loire Valley. Light whites may include Riesling, Chablis, or Grüner Veltliner; fuller whites might involve White Burgundy or oaked Chardonnay. Light reds include Beaujolais or Dolcetto, medium reds span Chianti and Merlot, and heavy reds encompass Syrah or Port.

In any pairing, one component usually takes the focus. As Master Sommelier Evan Goldstein notes, food and wine behave like two voices in conversation: one leads while the other supports. If attention should fall on the wine, the food is ideally a bit lighter; if the goal is to showcase the dish, the wine should be powerful enough to accompany it without overshadowing.

After weight, pairings often rely on either complement or contrast. Complementary choices match similar traits—for instance, an earthy Pinot Noir with an equally earthy mushroom dish. Contrasting choices embrace opposites, such as pairing an acidic, vibrant Sauvignon Blanc with a creamy sauce, allowing the wine’s sharpness to cut through richness. While complementing was once the dominant philosophy, contrasting gained popularity in the 1980s and parallels familiar culinary duos like salty and sweet.

Physical properties of wines

Although people often repeat that “taste is subjective,” certain taste sensations—such as bitter, sweet, salty, and sour—can actually be evaluated on a measurable scale, ranging from low to high. Flavors, however, like butterscotch, char, or strawberry, are not measurable in the same way; they are simply perceived as either present or absent. These flavors depend on smell, whereas basic tastes originate from the taste buds themselves.

Since individuals vary in their sensitivity to these sensations, many wine professionals rely more on these objective taste markers than on the more personal, non-quantifiable world of flavors. Wine expresses three core tastes—bitterness, sweetness, and acidity—each tied to a major component: tannins (bitter), residual sugar (sweet), and acid (sour). A fourth factor, alcohol, does not register as a taste but as heat, contributing significantly to the wine’s overall body. Depending on the dish, this heat can be toned down or intensified.

Acidity

Acidity plays a pivotal role in food–wine interactions because of its ability to sharpen flavors and stimulate salivation. In wine, acidity triggers a mouth-watering response, often heightening appetite. Wines tend to contain three principal acids—malic, lactic, and tartaric—each evoking distinct sensations such as green apple, creaminess, or slight bitterness.

Acidic wines excel with fatty, rich, oily, or salty foods, cutting through heaviness much like a squeeze of lemon brightens briny seafood. A dish that is tangier than the wine can make the wine feel thin, while a wine that seems overly sharp on its own may feel smoother when paired with an equally acidic dish. When the wine’s tartness mirrors that of the food, their acidity can neutralize, allowing other notes—fruit in the wine or secondary flavors in the dish—to stand out.

Sweetness

Sweetness in wine is determined by the level of residual sugar left after fermentation. Wines can range from dry to off-dry, semi-sweet, or fully dessert-sweet such as Sauternes or Tokaji. A guiding principle is that the wine should usually be sweeter than the food. Otherwise, the wine can appear harsh or sour, as when a brut Champagne is served with a sugary cake.

Sweetness also soothes spicy heat, making sweeter wines ideal for cuisines like Thai or Sichuan. It can highlight gentle sweetness within dishes or create a pleasing contrast with salt, as in the classic pairing of Stilton with Port. Similarly, sweet wines can balance tart dishes, especially those that already include a sweet-and-sour profile.

Bitterness

Bitterness in wine stems mainly from tannins, which produce an astringent, drying sensation and add structural weight. Tannins come from grape skins, seeds, and stems, or from oak aging. Because tannins bind to proteins, foods rich in protein or fat—like red meat or hard cheeses—tend to soften their rough edges, making the wine taste smoother and fruitier. Without protein, as in many vegetarian dishes, tannins latch onto proteins in the mouth itself, intensifying dryness.

Cooking techniques such as grilling or blackening can introduce a charred, bitter element that pairs well with tannic wines, whereas fish oils can cause these wines to seem metallic. Bold reds like Barolo or Cabernet Sauvignon may overpower delicate foods, yet they work beautifully with richer, protein-dense dishes. Conversely, spicy or sweet foods amplify tannin bitterness, often creating unpleasant off-flavors.

Alcohol

Alcohol strongly shapes a wine’s body, with higher levels contributing to greater perceived weight and density. In pairings, both salt and spice magnify the sensation of alcoholic heat. Likewise, a high-alcohol wine can increase the perceived heat of spicy dishes, making the combination feel far more intense on the palate.

Classification of wines

A first classification of wines is made by distinguishing between:

- Ordinary wines (all other types of wines)

- Special wines (fortified wines and sparkling wines)

Nutritional facts table of tomato fruit

Please note that nutritional values may slightly vary depending on the type of wine and can differ significantly for fortified wines. The table below shows values for Chianti Classico DOCG and can be considered indicative for non-fortified wines in general.

| Nutrients | Per 100 g |

| Calories (kcal) | 81 |

| Total fat (g) | 0 |

| ———Saturated fat (g) | 0 |

| Cholesterol (mg) | 0 |

| Sodium (mg) | 0 |

| Total carbohydrates (g) | 1 |

| ———Dietary fiber (g) | 0 |

| ———Total sugar (g) | 0.6 |

| Protein (g) | 0 |

Source(s):

https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vino

Photo(s):

1. André Karwath, CC BY-SA 2.5 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5, via Wikimedia Commons

2. Limbourg brothers, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons4

3. Tjeerd Wiersma from Amsterdam, The Netherlands, CC BY 2.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

4. bgvjpe, CC BY 2.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

5. User:Arnaud 25, CC BY-SA 3.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/, via Wikimedia Commons